End-month News February 2025

From Jim Harries

Dear Friends,

I have just come back to Kenya from Tanzania. I went on 8th Feb., and came back to Kenya on 22nd Feb. My major occupation, was two weeks of teaching at the Mennonite Theological College of East Africa, now renamed, the Mennonite College of East Africa. I taught the Pauline Letters to the certificate course, using Swahili.

Image below – my students for my two-week stay in Tanzania. Here they are after a Sunday service at a nearby church. (I did not accompany them on this visit).

Teaching at the Mennonite Bible college, I initially had 50 people in one class. This was challenging. It obviously required a change from my normal more participative teaching methods! A couple of days into teaching, the class was split into 3. Much better! I was left with one course; the Pauline Epistles. I did almost zero ‘lecturing’. Instead, I organised the students into triplets, reading, explaining, and preaching, from various chapters in the Pauline epistles.

I have discovered, that the college now has a website. See https://mceaafrica.ac.tz/ to find out more.

‘In order to teach, you always have to be reading’, one of my fellow teachers said to me the other day. I did not argue with him. His comment did cause me to reflect. The Mennonites who founded the mission were predominantly from the USA. Books available to read are mostly from the USA. The implication, then, is that the future of the church in Tanzania depends on its American links. I am reminded every day, whether I am in Kenya or Tanzania, of how differently people think here than do my America colleagues. ‘Perhaps African people should build on their own thinking’, I ask myself? This is how I designed my own teaching. In my course, on the Pauline Letters, I oriented students to read, study, then prepare devotional messages from, Paul’s writings, using Swahili, with no ‘theological guidance’ from myself … (In practice, of course, it is always good for students to be taught using a variety of approaches.)

A new sign-board for the theological college at which I was teaching. (It no longer calls itself a ‘theological college’, as there are visions of branching out to teach other things to make the college more sustainable.)

I do love some of the fellowships I attend with the Coptic Church when in Musoma, Tanzania. Similar-to yet different from, what we do in Kenya. In these fellowships, we arrive to find a cross sat ‘in location’ on a table outside the home of a church member. We gather around the cross, usually under the shade of a building, as it is late afternoon (5pm). The context is one of much poverty. Frequently a mass of children in attendance, plus a large group of women, and fewer men. What is great, that I do not experience in circles I visit in Kenya, is that following a message, people comment on the Scripture that has been taught, and how it has been articulated. An hour later, our small group that has come from the church, walks back again. So simple!

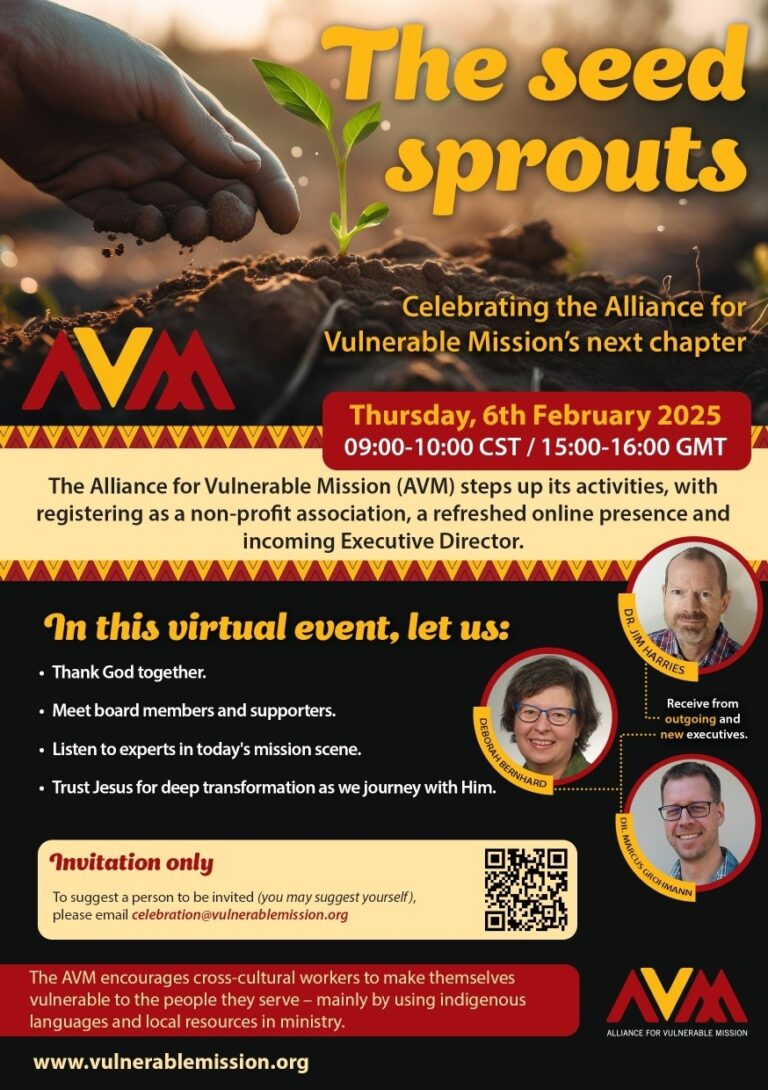

Alliance for Vulnerable Mission

See press statement here, regarding the transition event we held on 6th February: https://missionexus.org/press-statement-of-the-alliance-for-vulnerable-mission/

Home News

Sad news when I got home … was that while our rabbit (finally) gave birth … the cat ate all the baby rabbits. So, no progress on that side …

Trump and USAID

Staff here at the hospital dealing with ARV (antiretroviral) provision for AIDS sufferers, were laid off at the end of January. They have since been temporarily re-instated, as everyone waits to hear what is going to happen in the long-term. An ongoing cutting of the supply of ARVs promises, it seems to me, something little short of catastrophe for Kenya, and of course also for many other parts of the world.

Safeguarding

I have recently engaged some correspondence with my local MP in the UK, Kit Malthouse. I am hoping he may be able to influence legislators on safeguarding issues. At the moment there seems to be no provision for someone in my position. That is, someone who has had local children live in his home, and who has become de-facto guardian for the children. In more general terms, and of significant concern to us in the AVM (Alliance for Vulnerable Mission), safeguarding legislation assumes Western visitors to the majority world to be short-term providing emergency relief aid. Legislation seeking to encourage safeguarding seems to make it illegal for Western people to relate closely to Africans, encouraging a kind of segregation or apartheid. In the AVM we are encouraging missionaries to relate closely to indigenous people. This is likely to mean proximity to women, children and vulnerable people in contexts governed by localtraditional and not Western-designed, safeguarding systems. While major efforts are being made to extend Western safeguarding. This seems to be highly impractical. Indigenous systems are not perfect either. But it is difficult to get perfect systems.

Below is a copy of my (rather long!) most recent letter to my MP:

Dear Mr. Kit Malthouse, MP.

Many thanks for your recent response to my second email regarding my concern about being adequately safeguarded. I much appreciate your time and interest.

I am afraid that, on looking at the links and suggestions that you have given me, they have not been very helpful given my situation and circumstances. Perhaps a way forward would be to have a chat over zoom? If that is not straightforward for you, or in preparation for such a chat, please allow me to explain my situation in a little more depth and breadth.

Andover has been my home base since 1976. In 1988, Andover Baptist Church (now Andover Community Church) was my main supporting church, that sent me to Africa. I lived and served in Zambia from 1988 to 1991. Since 1993 I have lived and worked in Kenya, near Lake Victoria, not far from the African home of Barack Obama. I also frequently visit and serve in Tanzania.

My primary vocation in Kenya is Bible teaching. I do a lot of teaching in Bible colleges. I often teach in local churches and fellowships. Nowadays all my teaching is done using the Luo and Swahili languages. The Coptic Orthodox Church currently gives me my ‘umbrella’ with the Kenyan government. (Although I am not a member of their church.) This is since about 2018. Before that I was under an American Church, before that with a mission agency called SIM (Serving in Mission).

In order to be able to teach theology in contextually appropriate ways, in order to share God’s love with the African people, in order to help me to understand them better I have, since 1997, been looking after African children in my home. I am assisted in this by a Kenyan widow, a lady who was widowed in 1994, who before getting married it so happened wanted to be a Catholic sister, a dream that she now fulfils by devoting herself singularly to the care of orphans.

I have not built a house for the orphans. Instead, they live with me, in accommodation that I rent, in an African village. I have lived where I am now for 23 years. I rent two houses, adjacent to one another. This means that girls (and the ‘housemother’) can sleep in a house separately from where I sleep with the boys. (In the ‘boys house’, two bedrooms are used by the boys. I sleep in my own room.)

I have since 1997 had, on average, about 10 children stay with me at any one time. The housemother (the above widow) is the person who is there for them all the time. But this is also my home. I am the father figure. Some of the children have lived with me as the father figure since they were born. Others have come when older, say 10 years old. Many of those who have come when older have lived with widowed or single mothers, so for many of them also, I am the only father they have ever known. (In terms of a father who they live with.)

You will appreciate, that a group of 10 children would be very small to be an ‘orphanage’. To look after that small a group of children brings no legal requirement to register a project. The children are brought to me by local pastors, and we make an oral agreement with relatives for myself and the housemother (with whom I relate celibately) to become ‘in-loco-parentis’, or the guardians of the children concerned.

Because of the small scale of what I do, and because of its informality, while the government is aware of what we do, I emphasise, that it is not a formal project in any way. So nothing is registered, and nothing happens according to legal procedures. We simply operate through Christian love rearing the children in a Christian way, under the supervision of the local community, local churches, and especially my local home-church.

My home operates like an African home. You will appreciate that a lot of African families look after a number of children, some of whom are orphans. Were we to be ‘registered’ as an orphanage or something like that, then we might be legally required to keep various standards. This would set us, and especially the children, apart from other children in the community. Hence my preference for rearing the children just as they would be looked after if they were with another relative. This is a mode of caring for orphaned children which is recognized by the Kenyan government and is in fact preferred to formal orphanages, as it keeps the children located in a village and community setting.

In my home, and this is typical in the village, we do not have running water. Also typical, we do not have electricity. We cook local food purchased in the local market using charcoal, wood, and these days, often gas. The above-mentioned widow (who has 7 children of her own) is in charge of purchasing food and cooking, and the daily care of the children. I help her to do so by providing funds for food, school fees, children’s clothing, medical expenses (for routine issues like malaria) and so on. The widow and myself together make decisions regarding the welfare of the children.

I have long been very aware of the dangers of abusing children. Taking in orphans, you will appreciate, can be complicated. Hence we have always endeavoured to be as wise as possible to give the children the best care, given their African village context. Hence our home language is primarily Dholuo, also Swahili. I do not use English with the children. I have many safeguards in place, like: the constant presence of the housemother, always leaving the curtains of my room open at night until the children have all gone to their bedrooms, not having dogs or security guards, not paying the housemother or others who want to help us, restricting access to the children by visitors (especially those from Europe or the USA), having strict household rules and keeping to them. The children go to local schools and talk freely with everyone there. Villagers are constantly visiting us, and go in and out of my house as any other village house. We rent local fields in which we grow maize and beans. I or the housemother attend to issues with the kids at the local school they go to.

On the funding side, I do not accept any tied funds. I do not use my children as a means to raise funds. I refuse funds ‘for the children’. I only accept funds for myself. I as the father-figure use my personal funds to keep the children and the household running. I am enabled to do this, similar to many missionaries, as I receive funds from Churches in the UK and in Germany, and individuals who donate to me. I can keep the children on this money because:

- My house is cheap to rent as it is in a less-desirable part of a village a long distance from major centres of employment and a long distance from the road. Water is free, from a nearby spring. I nowadays (since 2015) use solar lighting (12v).

- I do not run a vehicle. Instead, I travel locally almost entirely by bicycle, and further afield almost always by relatively-low-cost bus-transport, as used by every other Kenyan.

My point is that the children I look after are as ‘my children’. Their (extended) families have informally awarded me ‘guardianship’. We are a ‘family’, and I am the (not-biological) father. A significant number of the children I now have are ‘grandchildren’, children of my children staying with me for various reasons. (This is very common in this part of Africa.) Hence I am the grandfather to them. There is nothing extraordinary about my relationship with them – it is in many ways simply that of a grandfather. When foreign visitors come, I am the one who gives them the kinds of rules that I notice safeguarding bodies (like Kids Alive International, whose details you sent me) advocate for. I agree with many of the rules. The only difference being, that I am the one giving others the rules, and cannot make myself subject to such rules. (You also pointed me to https://www.cfab.org.uk/, I have read through this, but it is not very relevant, as I am not trying to take anyone ‘across borders’. I have looked at this document: https://url.uk.m.mimecastprotect.com/s/1lQeCq7zvF8Av706sXhDSEbg96?domain=cdn.prod.website-files.com It does not pertain to my situation.)

My issue is, that unfortunately, none of the safeguarding agencies, and none of the regulations coming from the UK government, seem to anticipate that a British citizen can be in my position. To put myself into the place they designate for ‘foreigners’ would be to confuse everyone, to split the family, put children at risk, and to create a myriad of misunderstandings.

At the moment, some of the people in the UK who are supporting me are confused: Supporting me seems to contravene British charity laws. For me to try to keep the charity commission rules on some interpretations, is impossible, and/or would cause major problems, quite likely seriously spoiling the lives of children who I took on in good faith before stringent safeguarding laws were put into place. Frankly, even raising the issue of safeguarding in my village community, where it would come out of the blue, would seem to be to self-incriminate that I have been abusing children, which could put my life in danger (and thus again threaten the wellbeing of children in my care). In other words: my local community and local church(es) are my safeguarding community. This safeguarding system operates very differently to how the UK sees safeguarding, but it is still safeguarding.

I will add, that being now 60 years old, I am no longer taking in new children. The last child I have formally taken on will finish their basic schooling, at which my ‘informal’ responsibility for him will cease, at the end of 2028. At the same time, however, I notice that my home continues to be a popular destination for ‘grandchildren’, hence I at the moment still have 8 children fully in my care.

Just to make it very clear – I am a single man. I do not have sexual relationships with anyone. I have been convicted to remain single, something of course that the Bible promotes for serving God, so as to be in a vulnerable position from which to share the love of God with African people. I believe that more Westerners should be ‘vulnerable’ in this way to Africa.

The children do not ‘belong to me’ exclusively, but the task of caring for them is shared by members of the community. The above-mentioned widow housemother ‘lives-in’. I do not give her any salary. (This is unlike the situation anticipated by UK safeguarding regulations that assumes a British citizen to be wealthy and is concerned that they will pay-off people they are abusing. I do not make significant payments to anyone in my home community, outside of those people who actually live with me.)

Looking after children, especially orphan children, is always difficult. I can say that, by God’s grace, we have done very well. Children like to stay with us. We have had very few really difficult issues. The local community stands solidly behind us (which is not to imply that I and the housemother do not have full responsibility). When I read international safeguarding literature on caring for children, what is advocated for is what we do, but with respect to the local African community, and not a British or other European legal system.

I welcome visitors. In line with safeguarding literature – visitors who come from overseas need to be respectful, helpful, and polite. They should not stay for too long, or presume to relate too closely to the children. (It can be easier if they are familiar with the Luo or Swahili languages.) They should not ask probing questions about safeguarding concerns. (I think this is the same as for any family. Access to children by visitors is restricted. Visitors who endeavour to churn up division in the family by wrongly implying that abuses may be happening, are not appreciated.)

The current situation could lead to people assuming that ‘no smoke without fire’. Any kind of probe into my situation will easily imply that abuses are occurring, which given local tradition, could lead to victimization or even lynching of a supposed perpetrator.

I can add, given the above, picking on me as I happen to be a Brit, to be safeguarded UK style, while everyone else in the village remains ‘unsafeguarded’ by the UK, frankly seems unjust.

Note that the culture of the people I live amongst is very different to British-norm. As I try to relate to my children and others ‘as if I am a local’, it is very disingenuous to at the same time expect me to keep to the letter of British safeguarding regulations as if I am a foreigner.

I am not a lawyer. I have not investigated what appropriate legal-language regarding the case I am trying to make, ought to be. I am using layman’s English. Note however, that I am a widely published scholar – with around 27 peer-reviewed articles, and a dozen or so books. Much of my writing relates more or less directly to what I am here trying to communicate.

Hence my appeal to you, as my UK MP. I propose that you approach those who are responsible for producing international safeguarding legislation, to point out that they make no provision for someone in my position, and to ask them to rectify this situation. Preferably also, more urgently, I ask that I be certified as ‘safeguarded’, given that to not have such certification can sound very bad to people in the UK, as for some, wrongly, not to be safeguarded, is to be practicing abuse.

Yours very gratefully,

Jim Harries (PhD)

Missionary in East Africa

Jim