The Effectiveness of Short-term Mission to Africa:

In Respect to Westernising, Christianising and Dependence Creation

Presented at the Evangelical Missiological Society conference at the U.S. Centre for World Missions, Pasadena, California on 16th March 2007.

Jim Harries. November 2006. Copyright applies.

This essay is a personal attempt to address some of the much-discussed questions regarding the advisability and benefits of short-term missionaries. It is personal because I attempt to examine situations that are within my own experience. Although capable of broader application, I consider the situation of short-termers coming from "Western" countries such as Germany, America and UK to rural Africa, within the Protestant Christian tradition. I take the difference between "short" and "long" term missionaries as having less to do with duration, and more with orientation. A long-termer sets long term goals that prioritize vulnerability to the people and learning of language and culture. S/he will achieve the goals using local resources in a locally replicable way.

The answer to the question of the advisability of Western short-term missionaries depends on one's missiological model. Short-termers and post-career people are good at doing in Africa what they are used to doing in the West. If mission is "Westernising" then short termers may (but see below) be the best people to do it. If mission is to be encouraging people to improve on what they are already doing in their own culture, then how can short-termers do this, as they are unfamiliar with that culture? For example linguistically, short termers invariably promote international (European) languages. They will promote ways of doing church "like at home". They have no choice, as that is all they know.

I understand Western nations to be where they are now due to the combination of many circumstances over a long history. I take Westernisation ("development") as being an intelligent process involving interactions between old and new to bring beneficial changes. Short-termers to Africa are clearly not capable of engaging in such an "intelligent process", as they do not know the starting point of people in Africa. They do not know how aspects of their home culture can best be fitted into or onto their new host culture. Whether or not "the West" is a good thing, they are applying it blindly. If the new brings disorder and corruption then this is not a Westernising but a confusing process! Household furnishing like wardrobes are not advantageous to householders if left blocking the front door or sat on the kitchen table, so with aspects of "Westernisation" that do not fit local contexts. The new must not only be delivered, but it must be the right way up, and in the right place. [1]

This critique of Western "short-termers" is necessitated by the great power-imbalance that they are, whether they like it or not, a part of, that precludes "normal" relationships. It is often the motivation behind short-term mission, short-termers "go" because they believe they have wealth or knowledge of value to share. Otherwise; why go? What is to be shared is almost invariably "the Gospel and . . .", and it is that and that needs careful consideration. The contribution that Westerners make is invariably related to their relative wealth and the perceived "superiority" of their culture. This wealth and superiority is in turn the root of many of the problems besetting short-term mission efforts. The wealth and power imbalance in the world today makes it (in my view) very difficult for Westerners to share the true Gospel of Jesus Christ outside of the West without very careful self-depowering strategies.

This essay considers the role of short-termers primarily in relation to the societies being reached. It does not give detailed consideration to the important question of the care of the (Western) missionary force itself. Short-termers that are ineffectual or counterproductive in their impact on local people, may yet be a great asset or support to long-term missionaries. They could provide retreat facilities, pastoral care, child care or education, medical services, support connected with communication "back-home" such as maintenance of office and electronic or computerised equipment and so on. The suggestion in this article is that while such are important provisions for long-term missionary personnel, they should be minimised, and not be considered a part of the missionary outreach. That is, services that are provided to a missionary (and family) and even the presence of people providing the services if they are not adjusted to the local culture, create difficult problems when interacting with or when extended to host communities. [2]

Categories of Short-termers Five categories of short-term missionaries here considered are:

Post-career people typically reach the African mission field when 50 or older. They are often successful and well established in their home country - some so much so that they are able to fund themselves and perhaps a number of projects from their personal resources. The less able, less confident or less charismatic are less likely to reach the mission field. Hence this group consists of confident people who have already proved themselves at home, and now want to show that their gifts are as applicable elsewhere.

Experienced professionals are aged between 25 and 70. Unlike the post-career person, I assume the experienced-professional to be maintaining a Western career, of which his African involvement has become a part. Fields of experience may vary greatly, from computers, medicine, education, to theology, Bible teaching or preaching. These people may be big earners, are often very busy, and continue to be tied closely, perhaps in reality and certainly in their minds, to their home contexts and ways of operating.

Young and inexperienced people these days look for opportunities for broadening their experience of and exposure to the world before family and work commitments tie them down. To do this in a way of "service" is especially admired for Christians who are not primarily interested in pleasure or self-gratification. Such young people have a lot of energy and enthusiasm. They are especially keen to build relationships with age-mates in foreign countries. Some young people have limited means, but others may have significant resources at hand. These young people are typically single, and aged between 17 and 25.

Non-residential missionaries are to widely varying degrees communicating with and supporting indigenous African missionaries, church-workers or projects from "home". Their links with Africa began in many ways - sometimes meeting in the Western country, and sometimes a short-term (typically of a few weeks) trip to Africa. The brevity of these people's exposure did not prevent them from having profound often heart-rending experiences that they continue to recall and draw on to power themselves in their ongoing activities. These people may have little or even no on-the-ground experience of the cultures that they are reaching.

Island mentality is more and more common as the globalisation enabled by technology makes it easier for missionaries to live on the African "mission field" in a way largely independent from their surrounding community. A 10 year missionary who spends only 1 day in 10 acquiring quality exposure to local people is in a sense equivalent to a 1 year short-term missionary. For the other 9 days spent with family, watching TV, shopping or on the computer or internet, s/he may as well have been "at home".

What Short-termers can do: strengthen Westernised or Western types of institutions on the field. Short-termers can most easily and effectively be put to work in familiar (to them) contexts. It would go without saying that given unfamiliar contexts, they would not be able to fit as quickly or easily! They can be well utilized in perpetuating the work of institutions such as schools (that operate in Western languages,which almost all of them do), hospitals, mission administrations and so on. They may be usable in churches, depending on how Western and Westernising a church is. Other institutions could be added to this list.

A (if not the) key question in any evaluation of the value of short-termers on the African continent must be on the perceived value of such institutions (i.e. Western-based schools, bio-medical services, computerisation, complex church and mission administrations and so on). Related to this is the question of why such institutions should need foreign helpers, and why short-termers can function effectively in institutions that ought, presumably, to have become indigenous? The presence of short-termers will assist in preventing such institutions from becoming indigenous, thus frustrating this aim should it have been there. (As short-termers will put pressure on the institution to resemble the equivalent in the sending country). Have such institutions been set up by missionaries (and others) so as to remain as identical as possible to Western equivalents, or were they intended to become acculturated? The need for maintaining international standards and ways of operating can perhaps be seen most clearly with hospitals, where precise medical procedures of foreign origin need to be prescribed for scientific reasons. I would have thought that local innovativeness and adaptation would be considered more desirable in schools and even more so churches. On this basis, assuming that modern medical facilities are desirable, short-termers may be most helpful in hospitals, but a hindrance to acquisition of local relevance for other institutions. [3]

Apparent Advantages of the use of Short-termers

Renewed vigour, innovative ideas, different perspectives and the enthusiasm often engendered through novelty are not to be scoffed at. They are very often available from short-termers, particularly the younger ones. It could be argued that a short-termer can put up with difficulties that long-termers couldn't, because of the brevity of their stay. Certainly singles, young people, post-family people and even couples with young children can endure a degree of social isolation from their own societies that those with school age children shrink from. Someone could stick-out harsh physical conditions such as heat or lack of variety in diet for 6 months, who would not want to do so for longer.

On the other hand, it is probably also true that habituation, familiarity and deepening of relationship can soften the harshness of what is foreign. The shock of the reality of what is new and all too challenging can dampen enthusiasm. The non-fulfillment of anticipations can be depressing for a short-termer, whereas long-termers will adjust expectations to fit with reality.

Short-termers are often seen as strengthening links with their place of origin, especially their sending church(es). The value of doing this must depend on the philosophy of mission being operated on, is it enabling and strengthening the indigenous, or a bringing together of disparate peoples that is to be achieved? There is of course no guarantee that short-termers are the best way of linking distant peoples (or churches). They could breed distrust, unhealthy dependence, misconceptions and frustration. Certainly, the gross economic imbalance between West and non-West easily promotes dependence, to be explored further below.

Short-termers can fill vacancies that would otherwise be hard to fill. They are especially useful for filling spaces left by long-term missionaries on furlough. For a space left by a Western missionary to need to be filled by a fellow-foreigner though says something about the dependence being perpetuated in such mission. The argument that dependence is needed during the start-up phase is surely old hat now in much of Africa where missionaries have been busy for well over 100 years? Perhaps creation of dependence is a necessity, if the African cannot do what the missionary can do? If so then this needs to be acknowledged and become a part of the intentional life of mission institutions so that subsequent attempts at handing over not result in openings for corruption.

The problems of Short-term Volunteers

Having looked at how short-termers promote dependence, other disadvantages of their presence and activities connected to the relationships that they form are now considered.

The complexities of cross-cultural relationships are especially hard to comprehend without close knowledge of all sides. The meeting of Western with non-Western people can only ever be partial. That is, in the meeting of people of different cultures, parts of the culture of the "visited" group will remain invisible or at least inexplicable in the language of the "visitor", and vice versa. This results in mutual adjustment in behaviour in ways that people of neither culture will fully understand or articulate. Even if they can be articulated, it will be beyond the capabilities of the typical short-termer to take them on board, so they will make blunders.

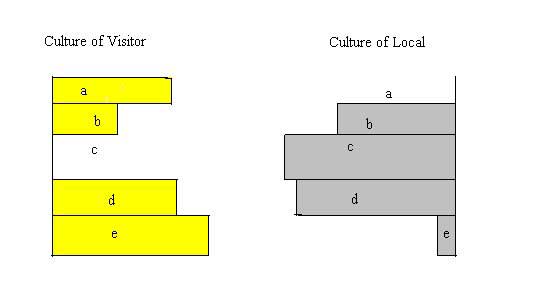

Let me illustrate this diagrammatically. If (very much simplifying) there were five cultural options, a to e, then two cultures may be as follows:

Fig. 1. Simplified representation of cultures

Because b, d and e are held in common, members of different cultures can recognise these in the other, even if their degree or emphasis varies. For example, handshaking is very widely known as a form of greeting, even though its frequency, warmth etc. varies widely between people. But the visiting culture does not have anything that corresponds to c in the local culture. The local culture does not have anything corresponding to a in the visitor's culture. Being unfamiliar with c (or a respectively) means that it is not likely to be seen. Yet these features not being visible does not mean that they do not have an impact on the life of "the other". A short-termer will treat the local as if c does not exist, but a long-term missionary will hopefully learn to adjust to c, even if it is not understood, according to its impact on life as a whole. In due course the long-termer may even perceive c. Circumcision and associated rituals in many African tribes could be an example of c, as many processes and activities are incorporated in them that a Western visitor could be totally unaware of. Another example is the prevalent fear of ghosts. It is in a sense even more difficult to give an example of a, because Westerners consider themselves an open book, and have long been promoting their culture around the globe. Yet a word in an open book that has no local-equivalent is impossible to translate into a local culture, at least unless or until it is experienced. [4]

Invisible parts of people's culture first become evident through their impact on the visible. Hence if only half of a tennis court is in view as a match progresses, the observer will conclude that someone on the other half must be hitting the ball back. It often takes a long time for a visitor to work out just what is filling what initially appear to be gaps in someone's sensible behaviour. Adjustments can be made by a sensitive foreigner in response to as yet unknown cultural components. For example, a visitor to Africa can realise the importance of not displaying anger before s/he realises that anger is generative of bad witchcraft powers.

The relationship between language usage and reality is particularly critical here. The dependence of language meaning on the context of its origin and use is rarely sufficiently appreciated. Many examples could be given. Many may appear negative to a Westerner. This is because they are different from what s/he is used to, and not because they are bad of themselves. So saying they will come at 8:00 am tomorrow may in East Africa mean that someone will come at 10.00 a.m. or not at all. "I am a business woman" can mean "I sell oranges while sat on the side of the road". "I value your friendship" can mean, "I want your money". [5] Saying, "I love God" may mean "I love money", if God's primary role is understood as providing money. "Cut the grass" may mean with a slasher by hand, and not with a mower. Such differences go deep and wide in language. One result is that short-termers generally do not understand what is being said or what they are being told by nationals. Not understanding is misundersting and misunderstandings can bring many difficulties.

Attempts by short-termers at engaging in dialogue with nationals, while admirable, can be problematic. Many people over the African continent being familiar with European languages means that there is no language barrier to prevent communication and therefore "misunderstandings" (see above) from occurring. Short-termers can easily say "stupid" or unhelpful things. For example, is it helpful to tell someone who earns $20.00 a month that if he was in America he would earn $2,000.00 for the same job (but of course the person would not understand that $1,000 of this must go on house rent, $600.00 on tax and $300.00 is needed per month just for food)? Is it helpful to describe the intricacies of courting in a culture where such behaviour is associated with gross immorality? Is it helpful to be pre-occupied in telling a people how wonderful English is, if they would benefit more from being proud of their own language, or how much your air-ticket costs if it is 10 years of a local salary, or the fact that in your country nearly everyone goes to university, implying that anyone who doesn't is backwards and primitive? Is it helpful to advise someone to do x, y, z when a fuller knowledge of the person's circumstances would reveal that x, y, z could not possibly happen? Is it helpful for a short-termer to make plans for a people that totally ignore a key part of their lives that happens to be invisible to him/her? (See Fig. 1. above.) And so on.

Not realising the deceptiveness mentioned above means that after a short while in the field, short-termers may no longer be ready to listen to those of "their people" with more experience. By this time, as early as just a few weeks after arrival on the field, they have already began to get their answers from nationals, from the horses mouth as it were, so why listen to the old missionary? The same short-termers, in relating "what the missionary said" to unfamiliar contexts can be turning helpful advice on its head. That is, the national could easily be offended in not understanding the reason or context of the words of long-termers to a short-termer, thus souring the long-termer's relationship with nationals. For example, a short-termer may be advised to learn a local language before engaging in a project. While this would help to ensure appropriate project-design, neither the national or the short-termer will necessarily see the advantages of this postponement in spending, until many years later. (Nationals will often not see it even years later if, as David Maranz suggests, their perception of "projects" is that they are primarily there to provide money and not to fulfill the various aims that a Westerner may have in mind for them. (Maranz 2001:151)) The long-termer seems to be imposing an unnecessary "drag" on the system.

There are many other ways in which the presence and actions of short-termers can widen the gap between the missionary and the nationals who he is reaching. One is the sheer time and effort needed from the long-termer to look after the short-termer. This includes in the planning stage, assisting in the arrival and orientation process, ongoing care, advice and problem solving and even farewell parties, plus all too often attention to correction of damage done by short-termers after their departure. Short-termers may be so opinionated as to bring more serious issues, such as attacking the long-term missionaries in open verbal ways. In some instances their criticisms may be accurate and important to hear, but in many cases they are rooted in insufficient understanding and can leave aggravation and bitterness in their wake.

A particularly difficult and sensitive issue is that of cross-cultural male/female relationships on the mission field. I get the impression that many Westerners are broadly in favour of cross-cultural marriage. While anyone critical of them may therefore well be scorned, such does not solve the problem of the disquiet arising when this occurs. My major issue with it is how it compromises and clouds Christian witness, particularly as an African making a "catch" of a Western spouse is comparable to landing on a gold mine. Economic and social differences between life in countries such a Europe or America and Africa are such that for an African man to get a White wife (and the other way around) is to gain greater economic advantage than (almost?) any other project or privilege that he could be given. The person gaining this advantage may or may not be a particularly meritable individual. Such an occurrence is certainly a major boost to prosperity gospel and seriously aggravates the situation in which missionaries supposedly carrying the Gospel of Jesus Christ are already valued primarily for their money. While from the point of view of the compatibility of the couple concerned many can argue the benefits of cross-cultural marriage, a missionary who is serious in promoting the Gospel will not want his primary reputation to be the provision of goldmines for local lads in the form of White women. (The process of forming such a relationship can of course be very damaging or at least distracting, whether or not it ends in marriage.) While it is clear to me that short-termers (or even long-termers) should not enter into "relationships" with locals, communicating this makes the host missionary to appear to be a prude. (More on this below.)

Finance and Short-termers

Issues with short-termers become especially difficult when it comes to finance. African people see G/god as the source of material prosperity in ways hard for Westerners to comprehend or believe. (Personal observation.) If efforts are not made to counter this, their interaction with Westerners will have them interpret Christian teachings primarily as ways to obtain money. It is my impression that many Westerners have not grasped how broad and wide these beliefs are, and how much "prosperity gospel" has become a hindrance to the acceptance of Christian truth, and to the development of African communities as a whole. (The prosperity Gospel orients people towards development through forming relationships with Westerners and through prayer, resulting in neglect of genuine hard work, planning etc.)

Most (if not all) missionary work from the West to Africa is integrally linked to financial provision. Numerous projects operate on this basis. A Western missionary never seems to be able to do anything that does not require vast (by local standards) quantities of money. The examples set by missionaries are usually impossible for nationals to follow. In their attempts to follow them, they may become liars, corrupt, and/or thieves. African nationals who try to follow missionaries examples become oriented to neglecting their own language, culture and traditions in favour of those of the missionary. Thus they exchange understanding for imitation. The only problems such nationals come to be interested in addressing are those the solution of which carry a reward from overseas. That is, relatively ignorant foreigners dictate (by the use of financial incentives) what should be local-originated problem-solving strategies, at the expense of local initiative. Corruption and even theft may be necessitated for the national to acquire the resources needed to imitate the missionary. Lying is in some ways inevitable in cross cultural communication, and is permissible in some senses in Africa that are condemned by Westerners. [6]

Short-termers are of little or no help in the light of these problems, because of their foreignness! They cannot help people to value and adapt or improve their own cultures or language, as they often do not have a clue about either. The Western habituation to solving problems by the use of money and provision of machines is grossly inappropriate (and damaging) in the long-term to many African contexts, but short-termers know no other way. Nationals meanwhile have become "yes men" and begun to understand that money is the answer to all their problems, regardless of the "evidence" before their eyes. (People can behave as if money is the solution to all their difficulties, even if it evidently is not.) Corruption is initiated or perpetuated as familiar Western transactions meet unfamiliar African contexts.

In order to help people to help themselves with local "materials" (or means of access to materials) an out-sider must first be familiar with the same. Short-termers by definition cannot have such familiarity. They will instead make locals dependant on that with which they themselves are familiar, i.e. the West! Very often short-termers will perpetuate such negative corruption-causing dynamics even after leaving the field, by trying to run projects, act as donors and give advice "from home". Such is increasingly facilitated by the spread of the internet and other cheap and convenient communication media.

Short-termers have many different impacts that go beyond their time on the field. Despite their having only limited understanding of field conditions, their ongoing familiarity and contact with home (Western) nations means that they may get a lot more attention at home than long-termers who seem to be way "out-of-touch". They end up on mission-sending boards that make critical decisions about long-termers. They have enormous influence over donor-flows. They acquire, in other words, great power over their church(es) mission strategy. The long-termer knows this. Because the long-termer's future, along with that of so many African nationals thus comes to lie in the hands of "those short-termers", long-termers will go to great lengths to please short-termers, to the neglect of what could actually be in the best long-term interest of nationals in Africa.

While the impact of money on the mission field is always dubious, short-termers are particularly tied to ministries based on its use, as without it they have nothing to contribute. (Whereas a long termer could use a local language in a local way to make use of local resources, a short-termer is by definition incapable of such through inappropriate habituation and ignorance of local conditions.) Do we need more missionaries who make locals dependent on foreign finance?

Under the Bowl.

The weaknesses of short-termers put their long-term hosts into a dilemma. If they are missionaries called by God then they should be given front-stage. Local people are very likely to want as much, particularly as their interpretation of successful missionary work is financial, and short-termers can be very lucrative. (Note that the African people's judging of missionary success by its financial contribution need not be "intentional". Rather, African values and the extended family system together act in such a way as to give a very high valuation to material advance.) At the same time, a host missionary may want to limit the "damage" done by a short-termer by restricting their movements and / or activities, and by encouraging them to be vulnerable to local people so as to be able to learn from them, and not immediately be in a leading / directing position. We have here a radical conflict of interests: popular and local pressure to elevate the short-termer to gain maximum financial advantage, as against senior-missionary pressure to restrict them and keep them "down" to vulnerable learning positions.

Such tension is hard to live with. The long-termer can easily seem to have hidden agendas, be selfish or some sort of prude. The long-termer's apparent failure to be in line with local people's wishes can be misread by all sides. This appears to be acquiring a lamp, then putting it under bowl! (Matthew 5:15).

But the long-term missionary, if he is a thinking person, will want to make conscious provision to ensure that the light he has an display be indeed that of the Gospel! A constant flow of short-termers can be like a flashing blue beacon alongside a candle. For someone wanting to sell candles, this can be a problem. Jesus himself did miracles and fed people. But he made sure that through all this people came to see God's truth. A true missionary must do the same, even if at times it means turning off that mesmerizing attractive flashing blue light called the short-termer. S/he should be given strict rules and guidelines, especially those that ensure language and culture learning. Especially, short-termers should be poor, i.e. not have money to artificially expand their ministry. There should be a commitment from the short-termer not to continue with relationships with people on the field after their departure. The wealth of the West meaning that local people often value foreigners exactly for their money means that a long-termer who tries to curtail a short-termer is at high risk of being considered as not having people's interests at heart.

In short, effective communication of God's word to a foreign culture requires attributes that a short-termer, as defined in this essay, generally does not have. Short-term presence almost invariably results in the predominant promotion of Western culture and Western funding. If this is not the aim of mission, then neither is the use of short-term missionaries helpful.

Redeeming the Short-termer?

So, has all been lost for the short-termer? I do not believe so. I share the following very brief recommendations to "short-termers":

1. While Western know-how and material prosperity may be a means to get people to places, they should not be what a missionary does when he gets there.

2. The power imbalance in today's world, is hard to dispute. Ignoring of this by planning mission strategies as if we are all like Paul the Apostle is naíve. (Paul had no regular support from a sending church, no wealthy country of origin, and no one to take action on his behalf when his listeners decided to stone him to death.) Paul was vulnerable in ways that missionaries from the West are definitely not. Scriptural teaching must be interpreted in context.

3. Short-termers can pay their way to acquiring once grandiose titles like "foreign missionary". But are they there to serve God, or to serve their ego, or have an experience?

4. I believe language to be of paramount importance. A good recommendation for a short-termer is to refuse to do ministry in Western languages. (See Harries 2006.)

5. I believe vulnerability to be of paramount importance. Short-termers who want to do effective ministry need to concentrate on making themselves vulnerable to the people. Such vulnerability needs to be combined with personal strength to avoid pitfalls that vulnerability can bring, such as sexual immorality, depression or inappropriate abuse. Then a testimony can be given of God's strength emerging despite human weakness.

Conclusion

This consideration of short-term mission rooted in personal experience in East Africa identifies the kind of short-termers here considered, then points out the importance of ascertaining the central goal of a mission enterprise as a prerequisite to discussion on their advisability or inadvisability. Short-termers can appear to be the most useful in strengthening Western institutions and providing capable enthused stop-gaps for long term personnel. Yet the ignorance of people unfamiliar with local contexts easily results in misunderstandings that may lead local people away from primary Gospel aims towards the prosperity Gospel and corrupt ways of life. For damage minimisation and effectiveness maximisation short-termers need to be vulnerable and ready to listen to long-term missionary counterparts, particularly on following recommendations such as operating from the basis of poverty and beginning with the learning of local languages.

Pressure from wealthy Westerners (and non-Westerners who aspire to wealth) makes it difficult to keep to guidelines suggested in this article. He who attempts to hold others to them is likely to be considered a prude. Economic forces of all kinds wielded by short-termers (advertently or inadvertently) are dictating missions policy, and increasingly overseas church's policy. That is a (unfortunate) fact of life. It is hard to see it changing without a major re-orientation in the ways that "the West" engages in Mission.

Bibliography

HARRIES, JIM,

nd, "Power and Ignorance on the Mission Field or The Hazards of Feeding Crowds". http://www.geocities.com/missionalia/harries.htm (accessed 15.01.03)

HARRIES, JIM,

2006, "Language In Education, Mission And Development" In Africa: appeals for local tongues and local contexts. (Unpublished paper. See www.jim-mission.org.uk/articles)

LEECH, GEOFFREY H.,

1983, Principles of Pragmatics. London and New York: Longman

MARANZ, DAVID,

2001, African Friends and Money Matters: observations from Africa. Dallas: SIL International

Endnotes

[1] It will be apparent that I consider "Westernisation" in this discussion of "mission", as these two processes seem at least from my perspective in Kenya inextricably linked, and not because I consider that they ought to be linked. Return to article

[2] The implications of such a policy run contrary to much Western thinking on human equality and seem to give missionaries a privileged status. Hence my emphasis that such provisions should be minimised. It is important for a missionary to show commitment to the Gospel in a way that makes sense to local people, and to avoid the perception that his/her support/ancillaries are a vital part of the message being presented. Should the missionary fail in this regard then his/her message will be one of "prosperity Gospel". It may well be helpful to provide geographical separation between ministry and support / residential facilities to avoid such corruption. See "dual identity" in Harries (nd.:7). Return to article

[3] This paragraph is a very brief treatment of a very complex topic. I have kept it brief so as not to distract from the main flow of this article. Return to article

[4] See pragmatic theory. E.g. Leech 1983. Return to article

[5] See Maranz (2001) for the relationship between friendship and financial dependence in Africa. Return to article

[6] This is a complex topic that goes beyond the scope of this essay. By way of example, simple differences in understanding of time can already be "lies". (He said he would come at 8.00am but didn't turn up till 10.00am!) African people's using words to avoid affront, even if such results in "untruth", may not be comprehended by short-termers. Return to article